A curious side-effect of the back-slapping Britpop era was the way the media's spotlight shone not just on the obvious band-generating locations (Manchester, Liverpool, Camden), but increasingly on roads less travelled, including Wales, of all places. The Manic Street Preachers were sort-of precursors to this trend, which by the mid-'90s saw attention given both to quirkily psychedelic propositions Super Furry Animals and Gorky's Zygotic Mynci and trad alt-rock combos Feeder and Stereophonics. Falling somewhere between these two camps were a band called Catatonia, who first came to my attention courtesy of their single Bleed. A short, snappy burst of indie-pop, it was both addictively effervescent and rough round the edges in an endearingly scuffed-up way. It also had a fantastically abrupt ending.

By the time Catatonia played the Joiners in January '96, the music press had started taking an interest, but singer Cerys Matthews was still happy to spend half an hour chatting to a student in the front bar before the venue opened. She was great company, and although I don't have a copy of the interview to hand I know that we soon got off the subject of music to have something resembling a typical down-the-pub conversation, at one point covering that classic (but now lost forever) topic of how strange it was that we were only four years from the end of the millennium. What neither of us knew at the time was that those four years would see Catatonia release two No.1 albums and Cerys become a genuine, written-about-in-the-tabloids, music-press-sexiest-female-award-winning star.

OK, so neither of us knew, but after seeing the band play it was clearly a strong possibility. The set drew on the yet-to-be-released debut Way Beyond Blue and saw both catchy pop tunes like Sweet Catatonia and You've Got A Lot To Answer For and moodier pieces like Lost Cat and For Tinkerbell. Cerys possessed undoubted starpower and seemed very much her own person - tougher than Britpop peers like Louise Wener and Sonya Madan, earthier than Bjork or PJ Harvey, boozier than any Riot Grrls and not obviously beholden to any of the classic female singer role models. (We wouldn't be talking about a male singer like this, would we? I'm afraid the latent gender imbalance in rock music and its attendant writing has seeped into my psyche). It would be a couple of years before Catatonia's big breakthrough, but they were definitely onto something.

The next show I went to spawned a more modest star; Sharon Mew, keyboard player/co-vocalist with Heave went on to join Elastica in their second incarnation, playing to significantly more people than bothered with the Papa Brittle/Heave show at the Joiners in March '96.

A few nights later, I was sat in the Joiners basement chatting to a bunch of thirty-something blokes who would have a worldwide smash hit single on their hands by autumn. The career trajectory of Baby Bird was a strange one: over something like 18 months, starting in July 1995, they released five limited edition full-length albums made up of home recordings made by mainman Stephen Jones. In Autumn '96, the full band would release a "debut" principally made up of slicker re-recordings of tracks from these releases, including the soon-to-be-ubiquitous You're Gorgeous.

I'd first heard Baby Bird on Mark Radcliffe's show on Radio One, when he'd played Hong Kong Blues and CFC off the debut lo-fi album I Was Born A Man. After this, we started getting review copies of the following albums at The Edge, and I began to rhapsodise about this strange, wilfully perverse and awkward songsmith, who appeared on his album covers having removed his face with a disposable razor (Bad Shave) and as a pregnant nude (Fatherhood). I wasn't alone; both the NME and Melody Maker fell hard for Baby Bird's early work, which resembled a perpetually pranskterish Pulp and could swing 360 degrees from one track to the next, from deliberately naff pop to seemingly sincere ballad, from megaphone-hollered noise sketch to end-of-the-pier comedy psychosis. My review of Bad Shave mentioned Sheep On Drugs, Portishead and Pet Shop Boys (as well as misquoting, rather brilliantly I thought, the Trashmen by suggesting that "everybody should have heard about the Bird") and concluded with the frankly unsavoury suggestion that, should "Steve James" (sic) become a star, he would almost certainly end up masturbating on live Saturday morning TV.

Just to clarify that point, he did (sort of) become a star, but he never pleasured himself on Live & Kicking.

Imminent fame always seemed that little bit less likely when spending time with a band in the fetid underchamber of the Joiners Arms, and it has to be said that Jones and his compadres did not look or act like a bunch of people with their hearts set on the charts. Highly sarcastic and self-deprecating men who were about the same age then that I am now, they resembled a down-at-heel Bad Seeds, sat there in their suits wondering when they were going to get shot of toilet venues and hapless student interrogators.

Several tunes off Bad Shave, including Bad Jazz and Shop Girl, had become running jokes between me and Matt Ross, my housemate frankly incredulous that both I and Mark Radcliffe liked Baby Bird. It was weird hearing the lo-fi tunes, possibly recorded in a bedroom and definitely listened to in one, translated to a conventional band format and performed, y'know, in front of people. But Jones proved to be a charismatically louche, if deadpan, frontman, and they aired a new song called - you guessed it - You're Gorgeous. It seems like hindsight talking when I say that it sounded like a hit, but it was certainly the tune which stuck in the mind most that night. I've got to say, the lyric "You took me to your rented motor car/And filmed me on the bonnet" immediately made it pretty clear that this wasn't the romantic piece which playlist compilers, ad agencies and wedding planners would later assume it to be.

I know what you're thinking - enough of this pop shit, let's hear about an underground hip hop/punk night, right? Good job my next assignment, just a few days later, was reviewing and interviewing King Prawn and Killa Instinct, then.

A tape of Killa Instinct's EP The Penultimate Sacrifice had made its way to The Edge and impressed me with its Gunshot-style UK hip hop sound and horror-based samples and lyrics. In person, Bandog and Geta were lovely, if slightly bemused that an indie kid student wanted to talk to them about hip hop. A year later, their next album would be shelved when their label went down, and the band would split, although it appears they've recently reformed.

King Prawn were a decidedly different proposition; hip hop was on their agenda, but not as much as punk and ska. Inevitably, comparisons to Dub War and Rage Against The Machine abounded, but they were more like a souped-up Specials, and their debut First Offence (on Welsh label Words Of Warning) went on to be a bit of a favourite of mine at the time. Pakistan-born bassist Babar Luck was a particular character, his mad eyes and bald head/big beard look making him the band's focal point and most recognisable member; he insisted that if I ever needed a place to kip in London I should get in touch and go and stay with his family, which wasn't, in my experience, a gesture which interviewees usually made. King Prawn would go on to be quite big in the UK ska punk scene, although in my opinion they never topped First Offence; vocalist Al Rumjen is now fronting Asian Dub Foundation, while Babar continues to make music under a number of guises.

The very next day, I was off to Portsmouth to catch up with Mega City Four. I'm pretty sure I interviewed them again, although I can't find any evidence of this. What I'm definite about, however, is that I went with a couple of girls I'd befriended from the year below me, called Debs and Linzi, who were the only people I've ever met who were hardcore Mega City Four fans. I have to admit that I rather fancied Debs, but if I was hoping to impress her by getting us all in to the show for free, it rather backfired, as this was one of the (many) instances in my life where a promised place on the guestlist has mysteriously failed to materialise.

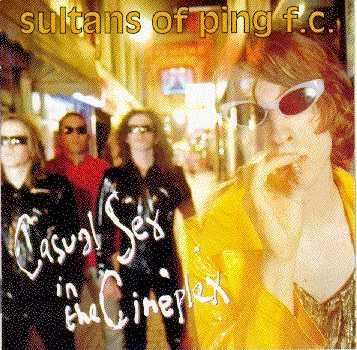

A few days later, and I was watching the Sultans Of Ping at the Joiners. This lot were mostly famous for Where's Me Jumper?, a novelty single which was one of the indiest records of 1992. Since then, they'd reinvented themselves as a PVC-clad rock'n'roll band, though in truth their tunes were still tinny, one-joke outings. Frontman Niall O'Flaherty was clearly having a ball acting like a massive cock, getting a roadie to light him a cigarette between songs and then hurling it, barely smoked and still lit, into the crowd as the next tune kicked in. At least, I think he was acting.

The next treat to draw me back to the Joiners was a double-header of Cable and Elevate. I decided that Elevate sounded more focused than they had done the previous year, with newer material taut and aimed straight at the gut, while comparing their frontman to Tim Roth and Jon Spencer.

Cable were one of the bands defying the dominant culture of Britpop and drawing influence from the indie rock scene across the pond. Perennial nearly-men, their closest brush with fame would come a year or so after this gig, when its use on a Sprite ad propelled their single Freeze The Atlantic to the dizzy heights of No.44 in the charts. They managed one last album in '99 before splitting; unusually, only the two people who'd drummed for them have done much of note since, with original sticksman Neil Cooper now in Therapy? and his replacement Richie Mills having done time in Sunna, The Lucky Nine and, er, MiLLS. Not entirely forgotten, a bunch of generally inferior bands contributed to a tribute album of Cable covers in 2006.

Prior to this Joiners appearance, I'd given Cable's re-released single Seventy a favourable review in The Edge. I can only imagine it was my suggestion that it sounded like Sea Monsters-era Wedding Present fronted by Tim out of Ash which inspired frontman Matt Bagguley to introduce the song by saying "This is not for the guy who reviewed us in The Edge". A long-forgotten acquaintance whispered in my ear that I should probably watch myself after the gig, as - in his opinion - Bagguley looked pretty hard. I couldn't see it myself - he was just a standard indie rock-looking guy, like Jonathan Donohue from Mercury Rev or somebody, but that year's Trainspotting had planted the Begbie-shaped seed that it's sometimes the small guys who are the real psychos. After the band's set, I decided to face up to things, possibly emboldened by a few pints, and approached Bagguley to tell him that it was me who'd written that review. He immediately made his excuses, telling me that he often struggled to think of things to say between songs and hadn't meant anything by it. I decided to let him off a good hiding.

Around the same time, I'd reviewed the single Straight Line by youthful post-hardcore types Tribute To Nothing and commented on one of the members' resemblance to little Billy Kennedy out of Neighbours (now a grown-up starring alongside Hugh Laurie in House). When I saw them at the Joiners, they didn't comment on it. Pretty good for nippers, though.

Time for something a little quieter, I think. My last review for The Edge as a student (I'd occasionally contribute after the best before date of my graduation) was of The High Llamas and Labradford at the Joiners, a venue singularly unsuited to the moments of grace and beauty at which these bands excelled. This gig was something of a quiet milestone, perhaps the first I'd attend which pointed in a different direction to the punk rock or more traditional indie shows I was frequenting, and as such a precursor to my ATP-flavoured future. I spoke favourably of Labradford, suggesting their "eerie soundscapes" could work as incidental music in Wim Wenders movies, although I also declared that their static performance meant they were a band better appreciated at home, late at night.

My fears about the Joiners as a suitable venue for the High Llamas seemed to ring true when the band's dual violin intro led to...nothing, as Sean O'Hagan found his mic dead and called a premature end to the song. However, their sparkly Beach Boys-with-a-dash-of-Stereolab tunes soon won out. Not sure about this video, mind.

And that was it. Spring 1996 marked the end of my university years, and, to be honest, I didn't have a bloody clue what to do next. At this point, I guess I'd be justified in saying TO BE CONTINUED...

Next time: love saves the day, Reading 1996 and my entry into the world of employment, possibly including another instance of my throwing up in Simon's car...